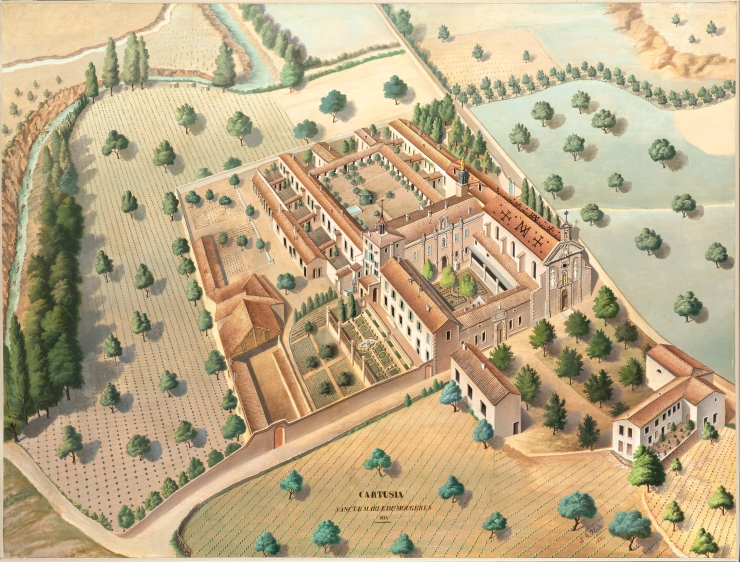

for the Charterhouse of Sevilla (Museum of Sevilla, Spain)

The history of the Carthusian Order is rich and complex. It is not possible to go into it in depth here. We will simply mention a few points of reference.

1. The origins

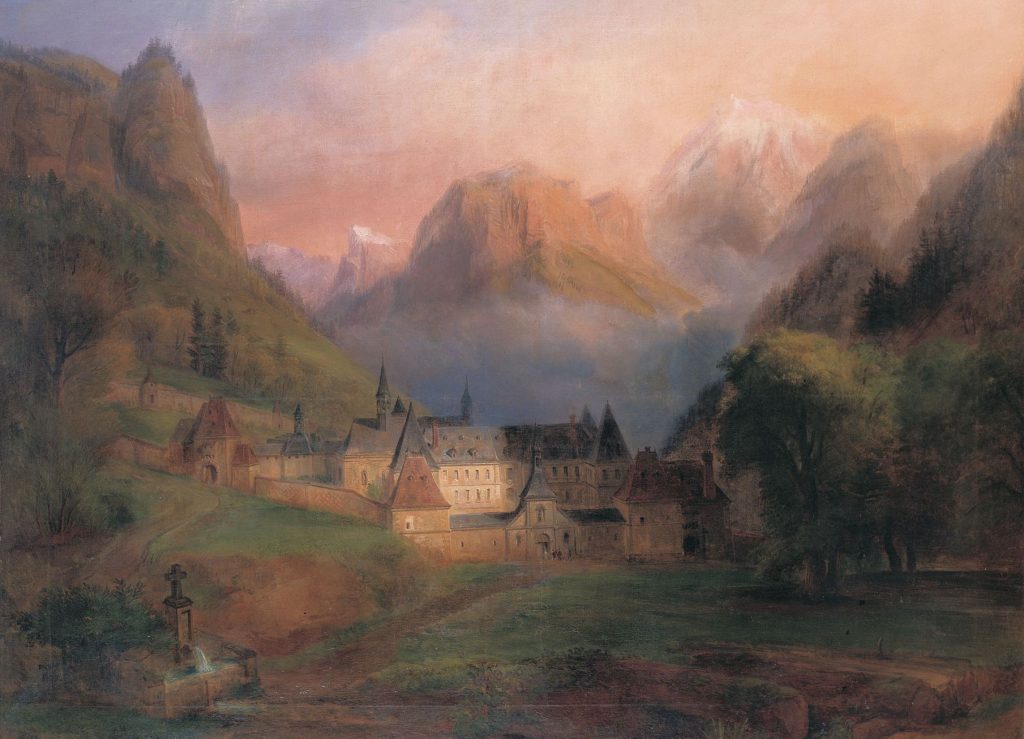

In June 1084, Master Bruno and six companions were led by Hugh, bishop of Grenoble, to the Chartreuse desert to establish a hermitage. The Chartreuse valley is a secluded place where Bruno’s soul could rise freely towards God, whom he sought and desired above all things. Bruno had to abandon his beloved solitude to obey the Pope, but soon afterwards, in 1090, he founded a second monastery according to his ideal/project of purely contemplative life: Santa Maria della Torre, in Calabria. Bruno did not leave a written Rule. Nevertheless, inspired by his example and formed by experience, the first Carthusian monks passed on this flame to their successors.

In 1109 the community of Chartreuse elected Guigo, who was only 27 years old, as its fifth prior. This act of trust was not to be regretted, for under his leadership a period of remarkable fruitfulness began. The fervour and fidelity of the first community would soon have a real influence: from 1115, several communities asked to join the solitary way of life instituted by Bruno: Portes (Ain), Saint-Sulpice (Ain), Meyriat (Ain), Sylve-Bénite (Isère), Bouvante (Drôme), Saint-Hugon (Savoy). These communities urged Guigo to write down for them the customs observed at the Grande Chartreuse. At the insistence of the bishop St Hugh of Grenoble, Guigo drew up the ‘Customs of Chartreuse’. In 1127, he completed this work in which he simply described the customs of his monastery. This work, which constitutes a true monastic rule, was adopted by these and new communities, Les Écouges (Isère), Durbon (Hautes-Alpes), Sylve-Bénite (Isère), Bouvante (Drôme), Saint-Hugon (Savoy), and remained the basis of Carthusian legislation throughout the ages. Under the benevolent vigilance of St Hugh, Guigo organised the Carthusian antiphonary, and left some other writings of great value.

In 1132, the Chartreuse community was put to a severe test. A large avalanche destroyed the original monastery. Six monks were killed, a seventh was found 12 days later; he was conscious but died the same day. Faced with such a disaster, Guigo transferred the monastery to a safer location, the one it still occupies today, two kilometres further down the valley. By the time of his death in 1136, the Order had nine houses.

The first General Chapter took place in 1140 under the leadership of St Anthelm, the seventh prior of Chartreuse. This Chapter established the liturgical unity of the houses. Shortly afterwards, the nuns of Prébayon joined the nascent Order.

2. The Middle Ages

From 1155, under the Reverend Father Dom Basil, the General Chapter met every year, always at the Grande Chartreuse. The Order was now organically constituted. The prior of the Grande Chartreuse, elected only by the religious of this house, received the prerogatives of Minister General.

(University Library of Glasgow, Scotland)

1160, first charterhouse in Central Europe: Seitz (in present-day Slovenia).

1162, first Nordic charterhouse in Denmark: Asserbo (Roskilde).

1163, first of the 22 charterhouses in Spain: Scala Dei.

1178, first of the 11 charterhouses in England: Witham.

Under the Reverend Father D. Jancelin, new liturgical guidelines were adopted and conventual Mass became daily. By the time of his death in 1233, there were already 47 charterhouses in Europe.

1257, foundation of the charterhouse of Paris by King St Louis. In 1300, the monastery of the Grande Chartreuse caught fire for the first time, then again in 1320 and it was almost completely destroyed. In the following centuries, the monastery was seven more times the prey of fire. In 1334, a charterhouse was founded in Cologne, the birthplace of St Bruno, which was to have a remarkable influence for several centuries.

The Black Death that devastated Europe in 1347-49 claimed almost a thousand victims in the Order. In 1370, the charterhouse of Rome was founded. In 1371, there were 130 charterhouses in the Order.

The Great Schism of the West, which divided the Church between obedience to the Pope of Rome or to the Pope of Avignon from 1378, also divided the Carthusians: the houses of France and Spain came under the jurisdiction of the Pontiff of Avignon, while the other charterhouses remained attached to the Roman Pontiff. It was not until 1409 that the Schism came to an end, and the Order was able to regain its unity the following year thanks to the simultaneous resignation of the Generals of both obediences: D. Boniface Ferrier (brother of St Vincent Ferrier) and D. Stephen Maconi (disciple of St Catherine of Siena). The General Chapter then elected as their only General the prior of the charterhouse of Paris: John of Griffenberg, born in Sax.

The foundation of houses continued at a steady pace throughout the late Middle Ages, reaching as far as Sweden and Hungary. The Netherlands knew a great concentration of chartreuses.

3. In the 16th-18th centuries

During the Renaissance, the Order was at its peak. In 1513 the Order recovered the house in Calabria, which had become a Cistercian abbey and had fallen into disuse. When the Reverend Father François du Puy, who had begun the process of canonising St Bruno, died in 1521 the Order had almost 200 active charterhouses. But this prosperity was not to last. Following the Protestant Reformation and during the troubles of the Wars of Religion in the 16th century, 40 charterhouses were closed. More than 80 Carthusian monks shed their blood for the faith, among them the very first martyrs of the English Reformation, in 1535. Several charterhouses were burned: the Grande Chartreuse was sacked and burned in 1562 by the Calvinist troops of Baron des Adrets. Many precious manuscripts were lost, including the original scroll of the funeral titles of St Bruno.

(Grande Chartreuse collection)

In times of turmoil, civil wars or religious wars, the Carthusian monks were sometimes forced to settle inside the cities: the charterhouse of Molsheim is a good example. Peace treaties were followed by a period of relative numerical stability. The Order had houses from the Kingdom of Portugal to the Duchy of Lithuania (the charterhouse of Bereza, in present-day Belarus, was the furthest house).

The Grande Chartreuse suffered another devastating fire in 1676, the ninth and last one. The Reverend Father Dom Innocent Le Masson had the monastery rebuilt according to a new plan, as it still exists today. This was only possible thanks to donations from all over the world. It can be said that there is not a single stone that was not donated by one or the other community of the Order. At that time there were about 160 charterhouses in Europe, which explains the importance of the buildings of the present Grande Chartreuse. Hundreds of people had to be accommodated during the General Chapter, which brought together the priors of all the houses with their retinue every year. At that time, the Order reached the number of 2500 fathers, 1300 brothers and 70 nuns.

(Private collection)

The Carthusian Order has always been very united. Only one independent branch existed in its history. The year 1785 saw the appearance of the Spanish National Congregation, the fruit of an ancient separatist spirit supported by the crown. But its existence was short-lived: it disappeared with the suppression of all the monasteries by the liberal government in 1835.

4. The French Revolution

In the 18th century, the closure of the 24 houses in the Empire of Joseph II of Austria was a harbinger of the Revolution. The revolutionary turmoil that swept through Western Europe shortly afterwards reduced the Order to very little: only a few houses remained in 1805.

(Musée Carnavalet, Paris)

The dominant principles of the revolutionaries were individualism and the absolute sovereignty of a secular state. Any particular grouping became forbidden so that only isolated individuals remained in front of the State. The period can be summarised in a few dates:

February 1790: The Constituent Assembly refuses to recognise monastic vows, considering them to be life-long servitude. The law first opens the door to those who wants to leave the monastery but lets the religious free to follow their rule and keep the habit.

12 July 1790: The Constituent Assembly votes the “Civil Constitution of the Clergy” and imposes the oath. The non-juring priests are persecuted. Several Carthusians are guillotined.

August 1792: Religious congregations are suppressed; it is prohibited to wear a religious habit.

October 1792: Deadline for the evacuation of the monasteries which become the property of the State with all their goods. All the French Carthusian monks are dispersed, some join the charterhouses in Switzerland or Italy.

1794: All the imprisoned religious under 60 years of age are deported to Bordeaux, Saintes and Rochefort, where more often they die in squalor. There were some Carthusian monks among them.

Several Carthusians led dangerous lives in hiding, among them Dom Ephrem Coutarel, the architect of the return to France when calm returned.

5. From the Restoration to the middle of the 20th century

A royal decree from Louis XVIII authorised the return of the monks. The Carthusians returned to the Grande Chartreuse on 8 July 1816. The same year, the surviving nuns resumed the Carthusian life at Beauregard (at Voiron, Isère). At the end of the century, which was a period of reconstruction, 27 houses have already been opened in Europe. Among them, the new charterhouse of Parkminster, in England, where the Carthusians were able to return for the first time after the Reformation.

However, a new rise of anticlericalism was emerging. The law of 1901 against religious congregations led to the simultaneous closure of 10 French charterhouses. The community of the Grande Chartreuse was expelled militarily by the public authorities in 1903, and settled in the charterhouse of Farneta in Italy. The other Carthusians had to emigrate.

The years preceding the Second World War saw the slow resettlement of some houses. In France, three houses of monks and one of nuns. In June 1940, the Reverend Father Dom Ferdinand Vidal, faced with the imminence of Italy’s entry into the war, took advantage of the situation by demanding the return of the religious to France as political refugees. The community was able to resettle in the Grande Chartreuse and the Order could hold the General Chapter in the Mother house again.

6. New horizons

In 1967 was elected the Reverend Father Dom André Poisson, whose task was to renew, with the help of all the members of the Order, the Carthusian Statutes following the Second Vatican Council and the new Code of Canon Law.

After the war, a number of monasteries were reopened or built. In France, Portes was restored in 1971 and Notre-Dame was built in 1978 to receive the nuns of Beauregard. In Germany, Marienau was founded in 1964 to receive the monks of Hain. In Italy, Trinità was built in 1994 to receive the nuns of Riva. In Portugal, Évora was restored in 1960 but closed in 2019. In Spain, Benifaçà was restored in 1967.

From the middle of the 20th century new horizons opened up for the Order, which began to spread outside Europe. First in the United States in 1950, then Brazil in 1984 and Argentina in 1998. The most recent foundations were in South Korea, one of monks, and one of nuns in 2002.

Finally, we can mention the historic visit of Pope John Paul II to the charterhouse of Serra San Bruno in Calabria in 1984, on the occasion of the 9th centenary of the Order, his letter to the Carthusians for the 9th centenary of the death of St Bruno in 2001, and the visit of Pope Benedict XVI to the same monastery in 2011.

The Carthusian Order has always been small in number compared to other monastic orders. However, it has endured through the centuries, with its share of troubles and profound transformations. The spirit of St Bruno is still alive, the mission of the Carthusians is still relevant, and the call of the desert continues to attract young vocations all over the world.

Frequently asked questions about history

7. The Carthusian Saints

As an old saying goes, “Cartusia sanctos facit, sed non patefacit”: “The charterhouse makes saints, but does not make them known.” In keeping with their vocation to the hidden life, the Carthusians do not have a postulator in Rome to request the canonisation of members of their Order. The only exception was in 1514 when the General Chapter asked Pope Leo X to canonise the founder. Most often the memory and cult of a Carthusian is the result of popular devotion. The first of all Carthusians to be raised to the altars was St Hugh of Lincoln, canonised in 1220 by popular acclamation and papal confirmation. The latest are Blessed Claudius and Lazarus, martyred with a group of other witnesses to the faith during the French Revolution, whose trial was promoted by the Diocese of La Rochelle in 1995. For this reason, the list below is not representative of the sanctity of the Carthusian Order throughout the ages, known only to God. Among them are several Carthusians who were known and admired because they became bishops, which is extremely rare. We present here briefly the Carthusian monks officially registered in the Roman martyrology.

(Charterhouse of Calci Museum collection, Italy)

Blessed Lanuinus, monk

Blessed Lanuinus the Norman joined the community of the hermitage of La Tour in Calabria, the second foundation of St Bruno, in 1091 or 1092. From then on, the charters were addressed to both him and Bruno, putting them on the same footing from an administrative point of view. Responsible for the temporal affairs of the community, he was elected Master of the hermitage after St Bruno’s death in 1101, despite strong opposition. From 1104, he was entrusted with missions by Pope Paschal II. In 1114, he added to the hermitage a coenobitic house, under the rule of St Benedict, for sick monks and where candidates for the eremitical life were to be trained. He died on 11 April 1116.

Blessed Ayrald, monk and bishop

Ayrald was first a regular canon of the cathedral chapter of Grenoble and attested as dean of Saint Andrew in that church from 1102 to 1132. He entered the charterhouse of Portes under Bernard, the first prior of that house. Only a few years after his profession, he was forced to accept the bishopric of Maurienne, where he signed charters between 1135 and 1143. As far as his episcopal office allowed, he remained faithful to the observances of the Order and liked to return to the solitude of Portes for short periods. He died on 2 January 1146.

Blessed John of Spain, monk

Born in Spain in 1124, Blessed John studied from 1136 in the cloister schools of Provence. In 1139, he took the monastic habit in a hermitage near Prébayon. But in 1141 he entered the charterhouse of Montrieux. Sacristan the following year and prior in 1148, he founded the charterhouse of Le Reposoir in 1151 and was its first prior. He gave the “Customs de Chartreuse” to the nuns of Prébayon and copied the Carthusian liturgical books for them, playing a central role in the affiliation of this monastery to the Carthusian Order. He died in office on 25 June 1160.

Saint Anthelm, monk and bishop

Born around 1107 not far from Chambéry to the lordly family of Chignin, Anthelm was first provost of Geneva Cathedral and canon of Belley Cathedral. He entered the charterhouse of Portes in 1136 or 1137, and was called to the Grande Chartreuse. He made profession there and became procurator immediately afterwards, before becoming prior in 1139. He convened the first General Chapter in 1140, resigned in 1151 and was elected prior of Portes. Later he was elected bishop of Belley in 1163. He tried in vain to mediate between St Thomas Becket and King Henry II of England. He died on 26 June 1178.

Blessed William of Fenoli, monk

Born in Garessio and initially a hermit, Blessed William of Fenoli, or Fenoglio, became a lay brother in the Piedmontese charterhouse of Casotto. A man of prayer and simplicity, he led a self-effacing life of service and fervent prayer. He died a hundred years old shortly before 1182. His reputation for holiness spread far and wide.

Blessed Odo of Novara, monk

Blessed Odo was born in Novara in 1140 and made profession at the charterhouse of Casotto. He was appointed first prior of the charterhouse of Jurklošter (Gyrio, Slovenia), but disputes with the bishop prompted him to go and ask Rome to accept his resignation. Passing through the abbey of Tagliacozzo, he was retained as chaplain and confessor by the abbess, a relative of the reigning Pope Clement III, and lived as a hermit outside the convent of the nuns. He was over 100 years of age when he died there on 14 January 1200. Several miracles occurred at his tomb and his cult remains very much alive in his diocese.

Saint Hugh of Lincoln, monk and bishop

Hugh entered the Grande Chartreuse where he was procurator. Later, at the request of the King of England, he was commissioned by the Chapter General to confirm the Carthusian life into that kingdom. He was the third prior of the charterhouse of Witham. After twenty-five years of monastic life he was elected Bishop of Lincoln. His zeal and wisdom were combined with a manly courage in the face of the claims of the civil authorities. This earned him the title of “Hammer of the Kings”. He laid the foundations of the magnificent Lincoln Cathedral. He was able to visit the Grande Chartreuse shortly before his death in 1200.

Saint Artold, monk and bishop

Artold, of noble origin, is linked by a tradition that cannot be verified to the Sothonnod family. Born in 1101, he entered the charterhouse of Portes in 1120. In 1132 he founded the charterhouse of Arvières at the request of the Bishop of Geneva and became its first prior. He no longer exercised these functions at the time of the General Chapter of 1140, or at least he did not participate in it. He is attested as prior in 1155 and during his unfortunate intervention in the conflict between priesthood and empire in 1164. In 1188 he was elected bishop of Belley, an office he accepted only out of obedience, but his 87 years of age forced him to resign in 1190. He returned to Arvières, where he died on 6 October 1206 at the age of 104.

Saint Stephen of Châtillon, monk and bishop

Stephen of Châtillon, born in 1155, entered the charterhouse of Portes, where he made his profession. In 1183 he was prior. After thirty-one years of Carthusian life, he was elected bishop of Die in 1207 and only accepted by formal order of the Pope and the Superior General of the Carthusians. He died in 1208 after a year as bishop and was canonised for the many miracles due to his intercession.

Blessed Boniface of Savoy, novice monk and bishop

The eleventh child of Count Thomas I of Savoy and Marguerite de Faucigny, Boniface of Savoy was granted the lordships of Rossillon, Virieu, etc. He entered at the Grande Chartreuse, but left by order of his father before his profession to receive the bishopric of Belley and the priory of Nantua in 1234. In 1239, he also received the administration of the bishopric of Valence on the death of his brother William. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 1241, he renounced his first two sees in 1242. He died at the castle of Sainte-Hélène in Savoy on 14 July 1270.

Blessed Nicholas Albergati, monk, bishop and cardinal

Born in 1375 to an ancient Bolognese family of nobility dating back to the 10th century, Nicholas Albergati studied law. He entered the charterhouse of Bologna where he was prior at the age of 32. After twenty-two years of Carthusian life, Nicholas was elected bishop of Bologna against his will, then created cardinal. A diplomat of great talent in the service of the Pope, he re-established peace between France and England. At the Council of Basel he defended papal supremacy, and later presided over the Council of Ferrara. Known as the “Angel of Peace”, he was universally loved for his holiness and goodness. He died on 9 May 1443.

Saints John Houghton, Augustine Webster and Robert Lawrence, monks and martyrs

John Houghton, born in 1487, took the degree of bachelor in both Civil and Canon Law at Cambridge. Ordained priest in 1511, he entered the charterhouse of London in 1515. Sacristan in 1523, procurator in 1526, he became prior of Beauvale in 1531, and soon after of London, in the same year. On 29 May 1534, he refused to recognise the supremacy of the king over the Church in England and did not take the oath imposed. On 13 April 1535, he was arrested with Dom Robert Lawrence, prior of the charterhouse of Beauvale, and Dom Augustine Webster, prior of the charterhouse of Axholme. Tried on 29 April, they were executed on 4 May and eviscerated. Fifteen other Carthusian fathers and brothers were martyred in the following five years. They were beatified on 29 December 1886 and canonised on 25 October 1970.

Blessed William Horn, monk and martyr

Blessed William Horn, a professed lay brother of the charterhouse of London, was imprisoned in 1537 with nine other brothers and fathers. While his companions died in prison during the year, he survived for three years and was martyred on 4 August 1540, disembowelled.

Blessed Claudius Béguinot and Lazarus Tiersot, monks and martyrs

Fathers Claudius Béguinot (born in Langres in 1736), from the charterhouse of Bourgfontaine, and Lazarus Tiersot (born in Semur-en-Auxois in 1739), from the charterhouse of Notre-Dame de Fontenay, gave their lives for the defence of the faith and the honour of the priesthood during the French Revolution. They died of misery, locked up on the pontoons of Rochefort, one on 16 July 1794 on board the prison ship ‘Deux-Associés’, the other on 10 August 1794 on board the ‘Washington’. They were beatified by John Paul II in 1995.

Other Carthusian monks, about forty, were also martyred during the Revolution for having refused to take the constitutional oath. Among them Dom Pierre Brizard was drowned on the docks of Nantes; Dom André Jacquet, Dom Marcel Liottier, Dom Michel Poncet, Dom Étienne Ballet and Dom Anthelm Monier were guillotined in Lyons at the end of 1791. Also Pacôme Lassus, Carthusian monk of Montmerle, guillotined in Pontarlier on April 25, 1794.

Other Carthusian monks, about forty, were also martyred during the Revolution for having refused to take the constitutional oath. Among them Dom Pierre Brizard was drowned on the docks of Nantes; Dom André Jacquet, Dom Marcel Liottier, Dom Michel Poncet, Dom Étienne Ballet and Dom Anthelm Monier were guillotined in Lyons at the end of 1791. Also Pacôme Lassus, Carthusian monk of Montmerle, guillotined in Pontarlier on April 25, 1794.

Other monks, without being canonised, have always enjoyed a reputation of sanctity within the Order, such as the Reverend Father Dom John Birelle (+1361), Dom Stephen Maconi (+1424) and Dom John Landsberg (+1539).

For the holy Carthusian Nuns, see their page on the website

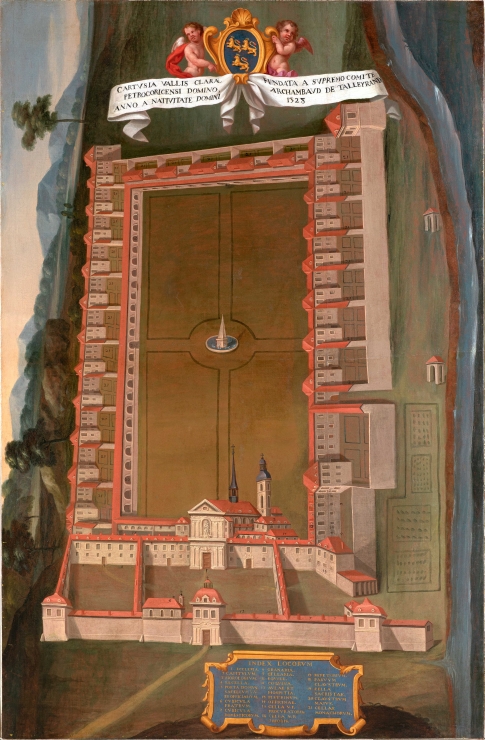

8. The charterhouses through the ages

Approximately 310 charterhouses have existed over the centuries; some have been in operation for a very long time, others have had a short life, some have been revived several times, others are quite recent. The carthusian geography has always been modified by the vagaries of history and by particular initiatives. All the houses of the Order throughout the ages are described in a supplementary page.

(Chartreuse La Valsainte collection, Switzerland)

(Musée de la Chartreuse de Molsheim collection, France)

(Charterhouse of Miraflores collection)

The “Cartes of Chartreuse”

La Grande Chartreuse has a precious repository of old paintings representing several houses of the Order. At the end of the 17th century, when he was rebuilding the Mother House, Dom Innocent Le Masson had monumental paintings made of each of the houses existing at the time. The tradition continued until the 19th century. These paintings, known as “Cartes of Chartreuse” (“Charterhouse maps”), always in a bird’s eye view, are an exceptional testimony to the life and faith of the Carthusian monks, as well as shedding light on their particular architecture.

Seventy-nine of these paintings have survived and were listed as historical monuments in 2001. They have undergone an ambitious restoration that has revealed their high historical and artistic value. We would like to thank all the patrons and public and private institutions that have collaborated in this restoration. This incomparable collection shows the impressive variety of Carthusian monasteries (styles), the variety of sites where they were built (deserts of rocks and forests, or near cities), and the variety of artists who made them (from the simple craftsman to the confirmed master). Finally, it is life in the Carthusian monastery that these maps illustrate, with a profusion of precious and sometimes tasty details, characters and scenes of daily life.

Slideshow “Gallery The Cartes of Chartreuse”

Other paintings representing the former houses of the Order (originals from the old collection, copies, or others) can be found in various monasteries and museums, especially in Austria (the Klosterneuburg institution has thirty-five paintings, twenty-four of them lended to Gaming). In many cases, these paintings are the only evidence of the appearance of the vanished monasteries.

(Klosterneuburg, Austria)

(Klosterneuburg, Austria)

(Klosterneuburg, Austria)