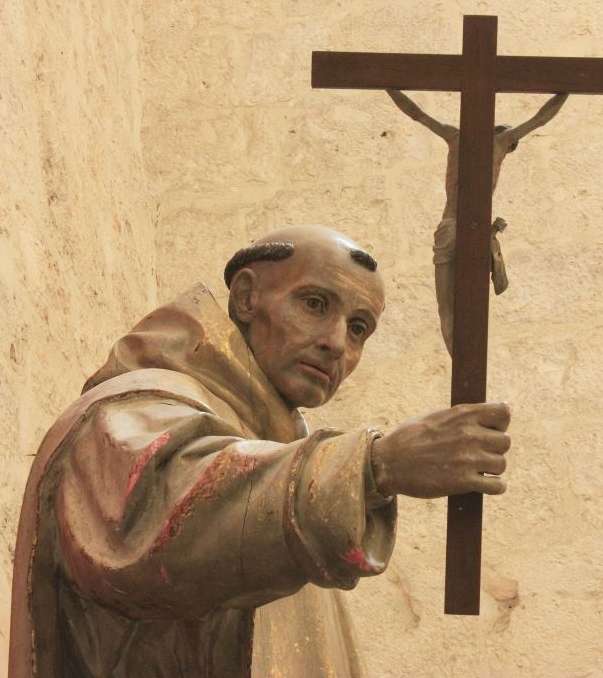

Charterhouse of Miraflores, Spain

Cologne and Rheims

Bruno was German1. He was born around 1030, in the famous city of Cologne, to well known parents2. As a young man, he was appointed canon of St. Cunibert’s Church. Early on, he came to Rheims to study at the illustrious cathedral school, formerly illustrated by the scholar Gilbert of Aurillac (later Pope Sylvester II). There he received a solid training in both secular letters and sacred literature 3.

Bruno became a canon of the Cathedral of Rheims, which ranked first among the Churches of the Gauls 4. In 1056, he was appointed rector of its school, one of the most prestigious of its time. He directed the teaching there for more than twenty years, being noted for his culture, his pedagogical qualities and the affection he had for his students.

In 1069, an unworthy archbishop, who had bribed consciences, was elected, Manassès of Gournay. He showed an insatiable greed for temporal goods, especially those over which he had no right. Then began a long struggle between a few honest canons, which included Bruno, and Manassès. Gregory VII put an end to this disorder in December 1080 and deposed the archbishop, ordering him to be driven out and elected another in his place.

Bruno, master in all honesty in the Church of Rheims, 5 was one of the most prominent candidates, he who had been deemed worthy of suffering persecution for the Name of Jesus6. But for him the time had come to answer a higher call and leave the world.

Chartreuse

Bruno then gave up all his assets, the honours associated with his office, the false attractions and the perishable riches of this world. Burning with divine love, he left the fleeting shadows of the world to seek eternal goods and receive the monastic habit7.

In June 1084, Bruno introduced himself to the young Bishop Hugh of Grenoble, who was very famous for his piety and culture, an ideal image of nobility of soul, of seriousness and of complete perfection.

Bruno’s companions were Master Landuino, who after him became the prior of Chartreuse; the two Stephens, that of Bourg and that of Dié – they had been canons of Saint-Ruf but out of desire for the solitary life, with the permission of their abbot, they joined Bruno; Hugh, who was called the chaplain, because he was the only one among them to perform priestly duties; and two lay people, whom we call convers or lay brothers, Andrew and Guérin. They were looking for a place that would be ideal for a hermit’s life, having not yet found one.

They arrived driven by this hope and attracted by the sweet scent of the bishop’s holy existence. He received them with joy and even with respect, discussed with them, and fulfilled their wishes. On his advice, with his help and in his company, they went to the desert of Chartreuse and built a monastery there.

Shortly before this, Hugh had seen God in his dream build a house in the desert for His glory; he had also seen seven stars that showed him the way. Now here were seven of them before him, which is why he gladly embraced their project8.

Life in Chartreuse

In his infinite goodness, which never ceases to provide for the needs and interests of his Church, God had therefore chosen Bruno, a man of eminent holiness, to restore to contemplative life the radiance of its original purity9. It was for this purpose that he founded and ruled the hermitage of Chartreuse for six years10, penetrating it deeply within his spirit11 and gave in his person a living rule to his sons.

St Peter the Venerable, illustrious abbot of Cluny and great friend of the Carthusians, gives a description of this kind of life similar to that of the Desert Fathers: “There, they continue to dwell in silence, reading, praying and also undertaking manual work, especially in the copying of books. Within their cells, at the signal given by the church bell, they perform part of the canonical prayer. For Vespers and Matins, they all gather in church. On certain days of celebration they depart from this pace of life … They then have two meals, they sing in church all the regular hours and all, without exception, take their meal in the refectory”12.

From this life devoted to God, in withdrawal from the world, St Bruno left some burning impressions :

“In any case, what benefits and divine exaltation the silence and solitude of the desert hold in store for those who love it, only those who have experienced it can know. […] Here they can acquire the eye that wounds the Bridegroom with love, by the limpidity of its gaze, and whose purity allows them to see God himself.”13.

Rome

But an unexpected event occurred: six years after Bruno’s arrival in Chartreuse, in 1090, Pope Urban II, his former pupil, called him to assist him with his collaboration and advice in the management of ecclesiastical affairs14. Bruno obeyed, and in spite of the pain in his soul, he left his brothers and went to the Roman Curia15.

His brothers, not believing that they could continue without him, dispersed, but Bruno encouraged them and managed to bring them back. However Bruno could not bear the agitation and manners of the Curia16.

Eager to regain his lost solitude and tranquillity, he left the papal court. Having refused the archdiocese of Reggio for which he had been appointed on the pope’s desire, he retired to a desert in Calabria called The Tower17.

Calabre

Thanks to the generous support of Count Roger, Norman Prince of Calabria and Sicily, Bruno continued with his project of solitary life, spent the rest of his life surrounded by a large number of lay people and clerics18.

Bruno wrote to his friend Ralph, provost of the Chapter of Rheims, a remarkable letter in which he evokes the new hermitage, called Sainte-Marie-de-la-Tour:

“I am living in the wilderness of Calabria far removed from habitation. There are some brethren with me, some of whom are very well educated and they are keeping assiduous watch for their Lord, so as to open to him at once when he knocks.”19.

Landuin, Prior of Chartreuse, visited him to discuss with him things of common interest concerning the establishment of the Carthusian vocation. On this occasion, Bruno, with his fatherly goodness, addressed a letter to his beloved sons of Chartreuse:

“Brother Bruno to his brothers beloved more than anything in the world in Christ: salvation in the Lord. I have learned, through the detailed and consoling accounts of our happy brother Landuin, how inflexibly and rigorously you follow a wise and truly commendable observance; He told me about your holy love, your tireless zeal for all that touches the purity of the heart and virtue: my spirit exults in the Lord. Rejoice, my dear brethren, for your blessed fate and for the largesse of divine grace spread upon you. Rejoice to have escaped the turbulent waves of this world, where perils and shipwrecks multiply. Rejoice to have earned the quiet rest and security of a hidden port”20.

The faithful Landuin died on his way back to Chartreuse, but the letter reached its recipients.

Death and glorification

In Calabria, Bruno applied himself, as long as he lived, to the vocation of a solitary life. It was there that he died, about eleven years after his departure from Chartreuse21, surrounded by the love and veneration of his brothers. They sent an encyclical letter throughout Europe, to announce to the churches and monasteries the death of Bruno, and to ask for votive prayer for his soul.

“Knowing that his time had come to pass from this world to his Lord and Father, he summoned his brethren, reviewed all the stages of his life since his childhood, and recalled with great wit the remarkable events of his time. Then he set out his faith in the Trinity in a profound and prolonged speech. And so on the following Sunday, October 6 of the year 1101 of our Lord, his holy soul left his mortal flesh”22.

A man thirsting for God, seduced by the absolute, but always discreet, his epitaph paints a beautiful portrait of his balance and his radiant personality:

“Bruno deserves to be praised for many a thing, but especially in this matter:

he was always a man of even temper, that was his specialty.

His face was always joyful, and he was modest of tongue;

he led with the authority of a father and the tenderness of a mother.

No one found him too proud, but gentle like a lamb.

In a word, he was in this life the true Israelite [a man without guile]” 23.

Charterhouse of El Paular, Spain

*

Bruno’s reputation for holiness had spread far and wide. The lay brothers who bore the encyclical letter could see that everywhere, in France, Italy, and England, the former master and founder of the Carthusian Order was known and revered. 178 eulogies or funeral speeches were collected, most of them in verse, which constitute a remarkable panegyric and show the place he had among his contemporaries.

Centuries passed, the Order spread, and the Christian world was rightly astonished that the Carthusians did not ask the Holy See for the canonization of their founder. They, in fact, merely followed in his footsteps, and in accordance with their vocation of a hidden life, had never applied for any of their own to be canonized… but an exception was required.

The General Chapter of the Order of 1514, under the direction of the Reverend Father General Dom François du Puy, a brilliant and cultured man, decided that the necessary steps would be taken. The Carthusian Order was at its peak; it had about 5600 religious, monks and nuns, who were divided into 198 monasteries throughout Europe. Leo X kindly accepted the Carthusian’s request, confirmed Bruno’s merits, and on 19 July 1514 authorized the liturgical feast of Bruno of Cologne by what is called an “equipollente canonization”, i.e., by a decree emanating from its own authority, without going through the usual canonization process. This inscription of Bruno in the catalogue of the Saints, and later, in 1623, the extension of his feast to the universal Church, aroused renewed interest in this spiritual figure.

His fatherhood remains alive.

DVD Saint Bruno, Père des Chartreux (excerpts)

- Magister Chronicle.

- Idem.

- Idem.

- Idem.

- Hugh of Die, Epistola Hugonis Diensis ad papam, PL 148, 745.

- Idem.

- Saint Bruno, Letter to Ralph le Verd, § 13.

- Guigo I, Life of Saint Hugh, § 16.

- Pope Pius XI, Umbratilem.

- Magister Chronicle.

- Pope Pius XI, Umbratilem.

- Peter the Venerable, Liber de Miraculis, Lib. II, ch. 27, PL 189, 943.

- Saint Bruno, Letter to Ralph le Verd, § 6.

- Magister Chronicle.

- Idem.

- Idem.

- Idem.

- Magister Chronicle.

- Saint Bruno, Letter to Ralph le Verd, § 4.

- Saint Bruno, Letter to his Carthusian Sons, § 1-2.

- Magister Chronicle.

- Encyclical letter of the hermits of Calabre.

- Funeral titles, § 1.